Philippe Tourriol, Nature’s silence

Philippe Tourriol is continually questioning, digging, breaking down the painting. Through his different mediums such as drawing, photography, installation… or oil painting, he asks himself: “how am I a painter?”

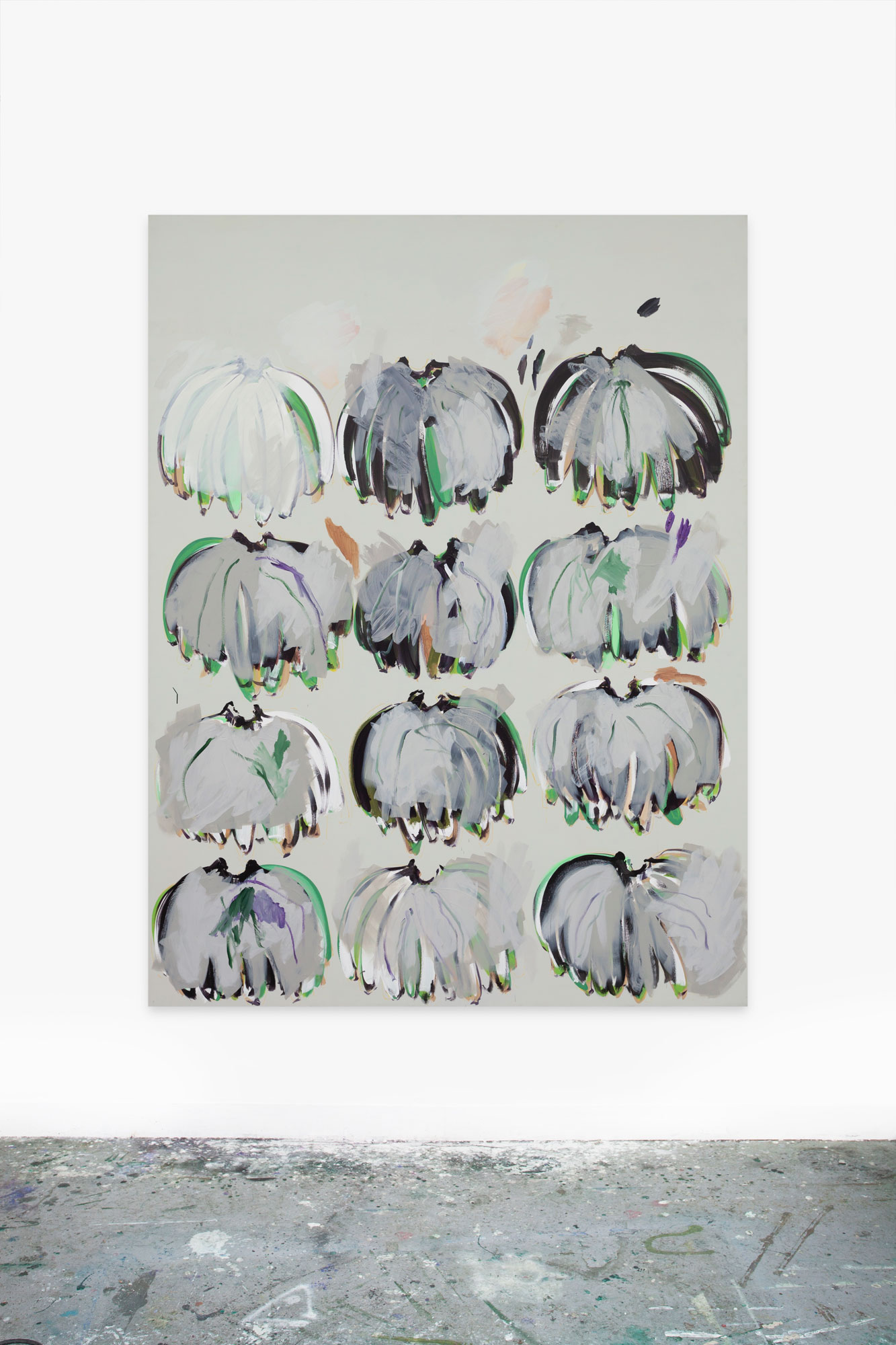

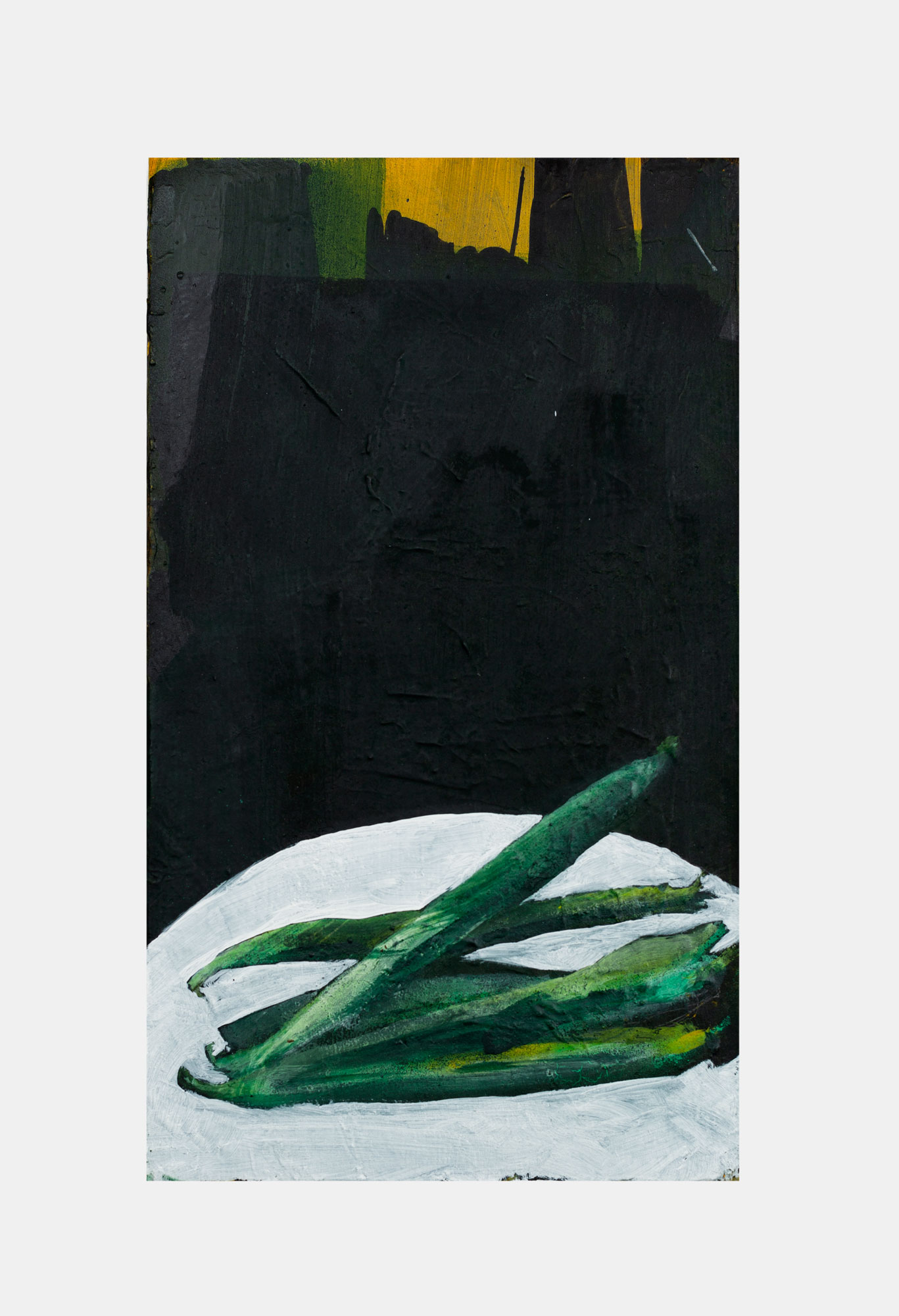

Philippe Tourriol is one of those artists who master the art of painting. He studied it, now teaches it and has been painting since the beginning of his carrier. For a time, he did massive canvas in the same way as lyrical abstraction, perfectly aware of the connections made with the American artists, a (sudden) distancing makes him stop in the 00s, what he thinks may be too easy. Rather than using color with vitality, he questions its meaning in art history and in philosophy. Drawing closer to his origins, everything seems to take him back to the Mediterranean Sea, narrated or dreamed. Outside of the color blue that comes from the imaginary, Philippe Tourriol uses endless shades of green, which he likes to grasp in the way of the glacis/glaze of Quattrocento, as much as spray painting, or conveying the paintings of Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot. In this return to fundamentals, reminiscences of childhood flow, in particular the mangoes gathered from the garden, referring then to seeds, fruits and animals in the artist’s mind. He also nurtures the history of flowers, which he wonders about its apparition in art and discovers, with Martin Heidegger, that their representations sharpen in the most conflicting times of the world…

Philippe Tourriol’s work is made of ruptures. From sharpened observations, while being snuggled up in the workshop. From deification of the nature, while living in a vastly urban universe. From a quick and fleeting move to draw, when the high-definition photographs refer to a long time, a suspended moment.While immortalizing very precise objects with his camera, the artist claims that he doesn’t care about the idea of subject. When getting closer to this perfect pixelized, we can understand that it is in the deeps of these oranges, grapefruits and creaminess of the (leaves of thoughts) that the symbiosis with the skin appearance is explored. That the citrons, arbutus or lemons are Talmudic or biblical references. Another key to understand….These pictures almost invoke a scent, transporting the viewer in another universe. The Oranais, from which the artist comes from, emerges at the same time as the French countryside and its interiors filled with trinkets or haloed with an old-world light. A Proustian dimension inhabits his world It may be that for him, the word photography seems too close to the concept of documentary, so he continually specifies that his pictures are pictorial. Evoking the name of Wolfgang Tillmans, for his formats and his blurs in the order of the painting, or this wanted confusion between real and abstract from Cy Twombly. Profoundly open in shapes, his work reconstitutes and feeds itself in a whole, in the way of a cycle in perpetual evolution.

— Marie Maertens, 2018

“Resonance” of Philippe Tourriol’s painting

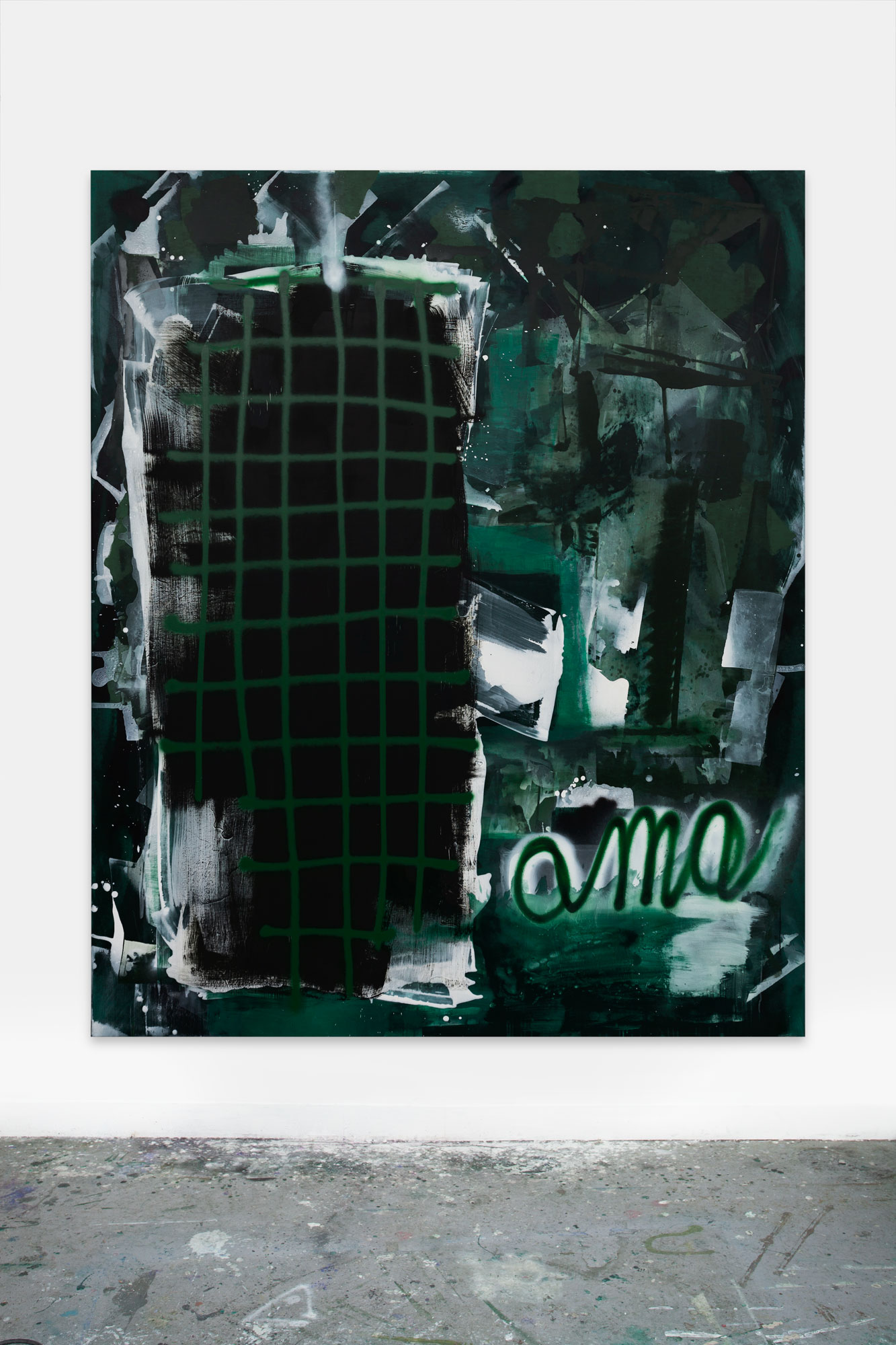

The great teleological narrative of modern painting aimed at the advent of “pure painting”: abstraction. This path provided an opportunity to raise the art of colour to new heights, by combining this quest, in the work of several great abstract painters, with an affirmation of and play on the “grid” as the underlying framework of the painting. Between Mondrian’s quest for universals - the right angle and trichromy - and Klee’s fragile and sensitive “multicoloured parterres”, Philippe Tourriol and the abstract painters of the present generation have had to find their own way, appropriating or recycling - with a paradoxical mixture of devotion and irony - the fundamental elements of modernist abstraction.

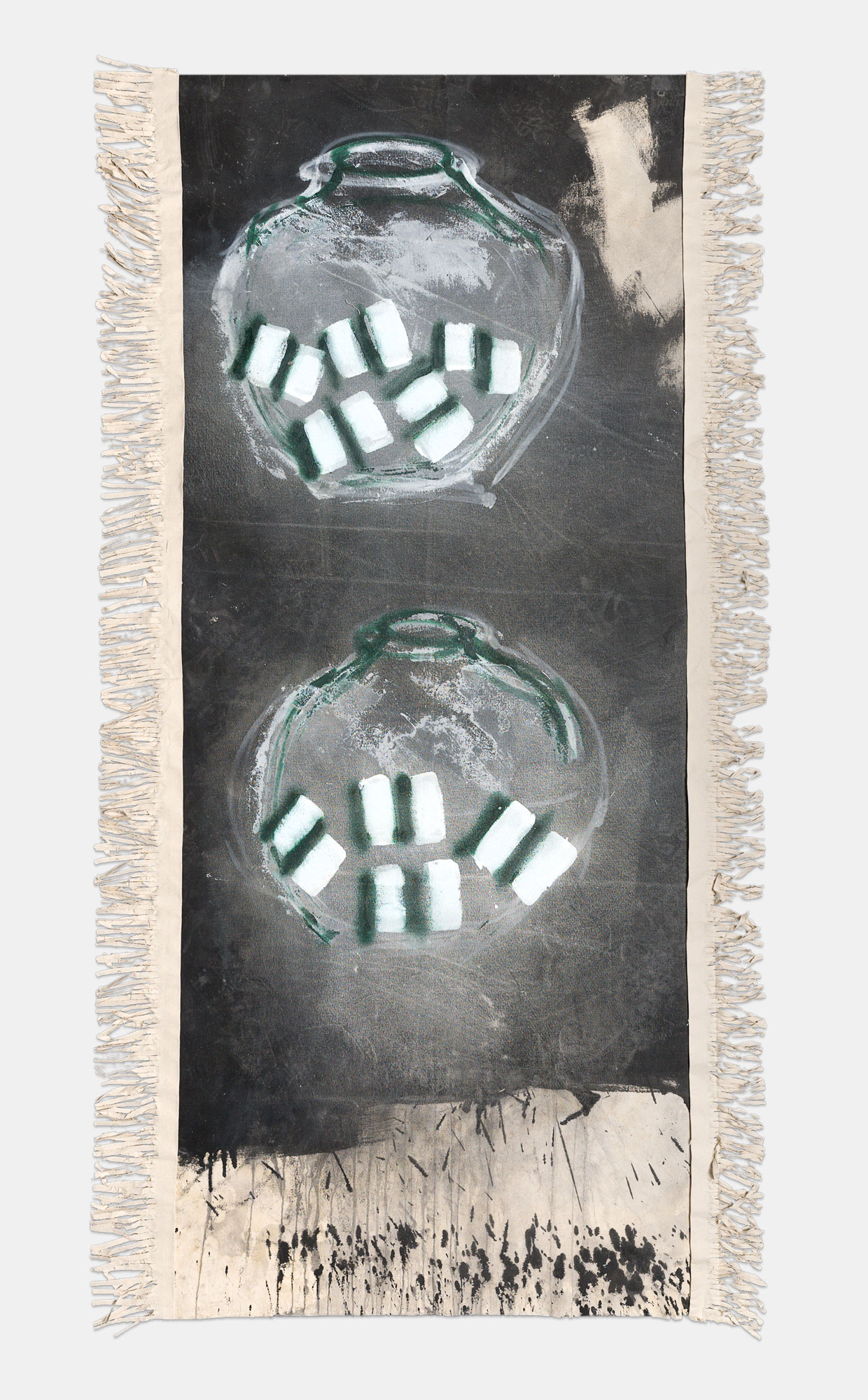

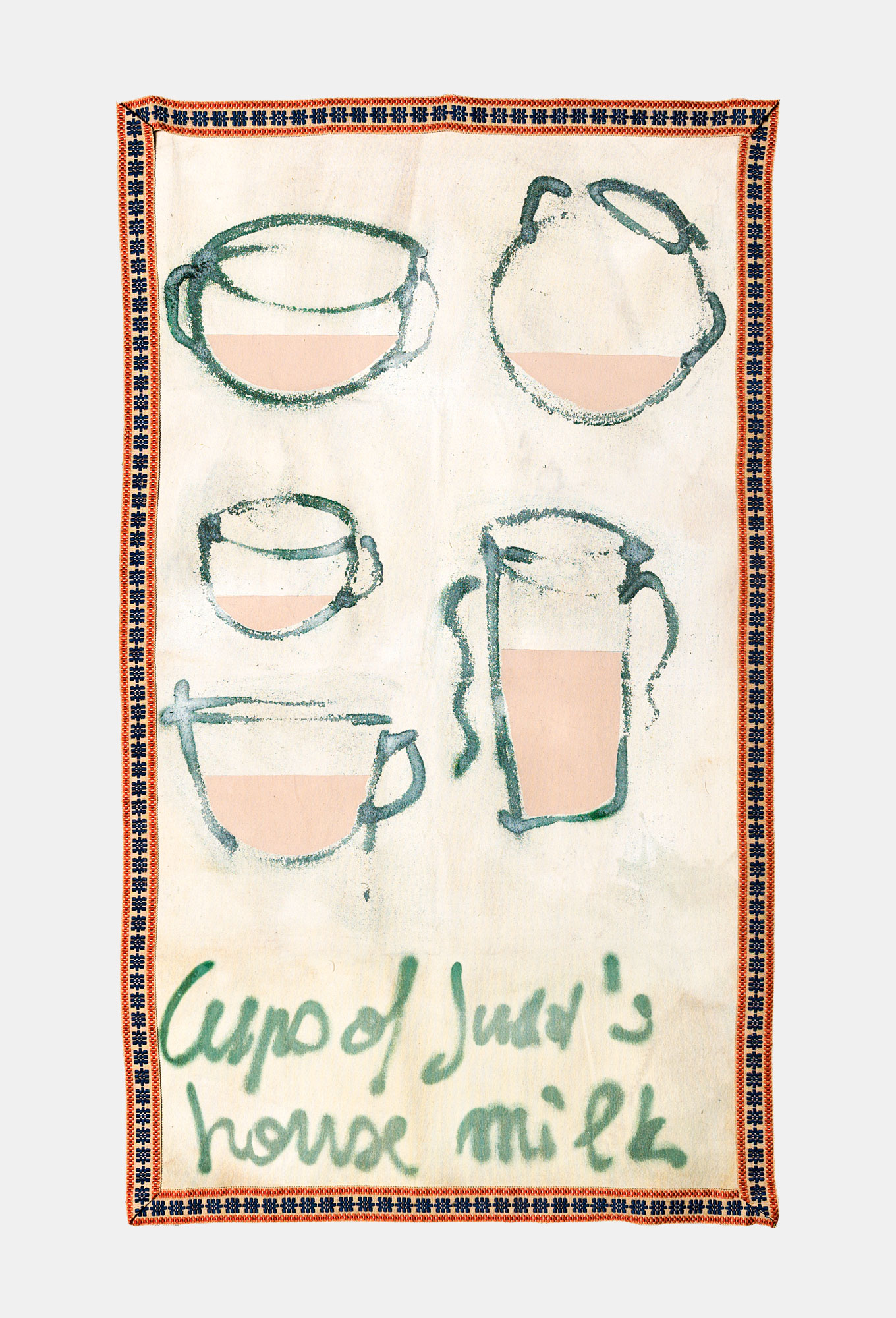

I also note that part of the founding narrative of modern painting, upstream of abstraction, was constituted by “a history of pots”, and Tourriol may certainly have been aware of this. One thinks of the distorted pots and compote dishes in Cézanne’s still life; but also of the legion of pots, carafes and absinthe glasses, deconstructed and reconstructed by Picasso, in search of a pure space for visual experimentation (the pot was later to become for Picasso the very support of painting, of a spontaneous and hedonistic painting, rich in quotations...).

Philippe Tourriol may well have been thinking about this remanence of the pot at the dawn of modern painting, when he produced his new paintings. In any case, the pot in Tourriol’s paintings is not a restored illusionist figure, but rather the initiator of a reverie or a memory, perhaps the memory of a founding motif of painting; and, beyond that, the thought of an ancient and universal archetypal form, with feminine connotations, referring back to the origins of the material manufacture of objects, and perhaps also to the foundations of the art of sedentary societies. As prehistoric and ethnographic research has shown, this original pot may embody a reproductive and protective form, containing fertile water, then oils, seeds, medicines and the alcohol used in libations; but it can just as easily be seen as a mournful and funereal form, containing the effects or ashes of the dead.

Looking at Philippe Tourriol’s pots painted on “free” canvases (without stretcher), and seeking to perceive their “resonance”, I take the liberty of once again making a diversion into the factory of Paul Klee’s painting. Like Tourriol, Klee was coming of age as an artist, and in 1921 he paid homage to the pot, to pottery, and perhaps to the “potter-demiurge”, by painting two remarkable watercolours: Topferei (Pottery) and Fuge in rot (Fugue in red). Klee certainly saw this focus on the pot and its variations as a reference to the universal archetypal form of the container. But in both Klee’s and Tourriol’s paintings, it seems to me that the pot appears as an almost “sonorous” object, which can be heard singing through repetitions, regular or irregular stanzas, more lyrical outbursts and chromatic vibrations. In one of his large dark canvases spread out on the floor, which Tourriol shows me in a photograph, the painter evokes the pots by their contours, and these seem to want to clash, overlap and sound like resonators, creating a kind of optical polyphony in the space of the canvas.

Finally, as I am very aware of this relationship between pottery and painting, or rather the incorporation of pottery into painting, I would also like to mention the very serious parallel established by the art historian Meyer Shapiro between the sedentarisation of human groups in the Neolithic period, agriculture, the (geometric) parcelling out of space, the invention of a new form of painting (very different from cave art) ... and the invention of pottery. According to Shapiro, who has been trying to establish the “humanity of abstract art” since prehistoric times, the new painting of the Neolithic period was based on the visual and textural occupation of a specific background and frame, a finite rectangle, abstract and mobile, cut out of bark, skin or canvas. It is this closed, active and dynamic field of the canvas rectangle that will host the “imaging substance”, i.e. the lines, contours, stains and outpourings of paint. In this way, the free canvases Tourriol sometimes lays on the ground, held in place by stones, are the place where archaic pots emerge and “speak”, like a reminiscence of the forms on the original canvas, affirming its materiality and its frame, in other words a fundamental matrix where all the gestures, signs and imaginings of the painting to come can emerge.